In his 2011 GDC presentation, The Identity Bubble – A Design Approach To Character and Story Creation, designer Matthias Worch builds on the work of Gary Fine (From his book Shared Fantasy: Role Playing Games as Social Worlds), using the conceptual model of frames to examine how players have multiple, often conflicting, internal voices. During play they are at once, people, players and characters, with different motivations operating within each frame.

Games allow us to participate in defining the behaviour of a character, our actions become theirs, our choices influence their behaviour. The player frame takes the lead in defining motivation and performing action. One common occurrence is the imposition of our desires upon the character, as Worch describes it: “This is the reason we play games: the ability to drive the action, to express ourselves, to lead.” As players our desires often lean towards efficiency, we may even strive for optimality when characters in fiction rarely do. When the player and character frames begin to drift apart, when our motivations as players no longer match those of the characters we are playing, we complain about dissonance. Our chosen approach determined within the player frame does not match that supplied by the fictional context within the character frame.

Frequently there is no choice, the game can’t be played in a way that doesn’t foster such dissonance. Even if you try the mechanics of Assassin’s Creed don’t allow for the efficiency it tries to fictionalise as being part of Altair’s character. In such instances, where the only options available are those that contradict the established narrative context, criticisms are justified. Worch’s method for avoiding this drift is to find ways that encourage the alignment of the character and player frames.

A commonality of each of the presented methods is that the character frame should be adjusted to align with the player frame. What of “self-correction”, of playing in a manner that is appropriate to the character; in so far as the abstracted nature of game mechanics allow? What if instead of determining the behaviour of characters based on the our motivations within the player frame we modify our behaviour to better fit the context of the character we are playing?

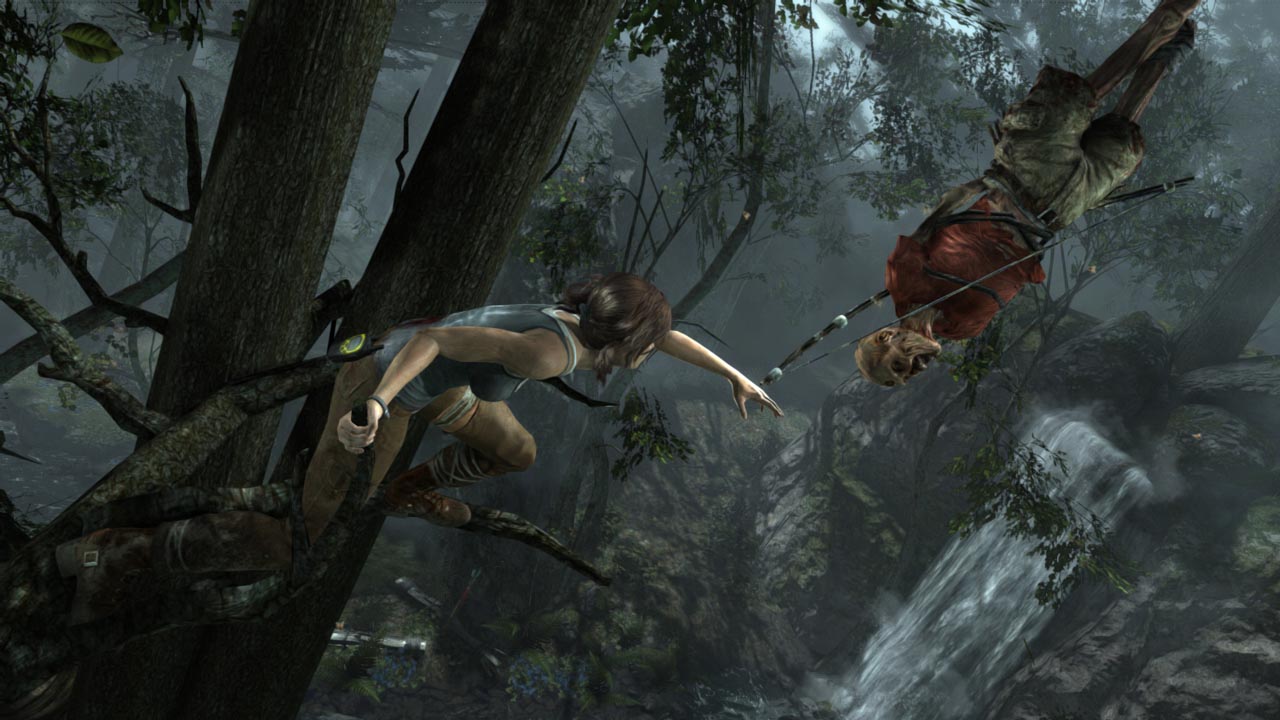

Early in my time with Tomb Raider it became clear what the game wasn’t going to do. The narrative is a tale of survival and growth, of overcoming extreme hostility. The mechanics you interact with to progress that narrative are high level abstractions of those concepts rather than attempts at simulation. Tomb Raider is, not a game about survival from a mechanical perspective, there are survival elements though they are heavily abstracted. Tomb Raider is a game about hostility and overcoming that hostility as a means of character growth. This basic conceit is presented and reinforced within the first ten minutes, as a Lara scrambles out of the cave she finds herself in though a variety of Quick Time Events and context sensitive actions.

The manner in which Lara obtains a handgun, and in the process kills for the first time is messy, violent and problematic in several ways. Shortly after that she is confronted by others of the Solarii, the cult like inhabitants of the island. It’s possible to kill them quickly and relatively cleanly, it’s also possible to keep shooting them until they stop moving. Without intending to I made the choice that being highly efficient wasn’t appropriate or necessary. When time slowed down in that first encounter instead of using it to line up precise shots, I fired as soon as the gun was pointed at the Solarii and didn’t stop until he collapsed, then I did the same with his companion; I did what I felt Lara would do.

This is a pattern I repeated throughout, it stopped being a conscious decision almost immediately. I was not directly punished for being inefficient and messy, and the narrative and characterisation did nothing to contradict my behaviour. Initially it had been an experiment to see if I could get away without turning Lara into the “alpha predator of ‘headshot island'” and it was possible, furthermore it felt emotionally resonant in a way I believe being efficiency wouldn’t have.

Throughout the next few hours when confronted with armed hostility I played in an improvisational way, explosive barrels, fire arrows, horrific melee kills; every tool at my disposal combined into a mess of violence. I was mad at the Solarii for what they were doing to my friends and to me, and I took that out on them. Why use one bullet when I can use five? Why use a normal arrow when I can use a flaming one? I scrambled around, dodging attacks, stabbing people in the legs, smashing rocks into faces, screaming, swearing. It was a nightmare of brutality and violence. Once it was all over there was no Nathan Drake like quip just an exhausted sign of regret tinged relief, both from myself and Lara. Neither of us wanted to be doing this much fighting but if we wanted to survive we had little choice.

I had not modified my overriding motivation, I wanted to be entertained, to have a memorable experience, and I was, I did. What I had done was slightly modify my behaviour. To keep the “identity bubble” intact it is necessary to make adjustments to at least one of the three often conflicting frames, to correct for drift. Which frame needs correcting and who performs that correcting does not always need to be the same for every game.

Games are participatory, a shared construct of designer and player. It’s not uncommon to talk of how games should react to player behaviour, taken to an extreme this can become the arrogance of agency, the notion that it is the responsibility of all games to acknowledging and response to our behaviour no matter how unpredictable or contextually inappropriate. If games are about shared authorship don’t we, as players, have a responsibility to ourselves to move beyond “willing suspension of disbelief” into actively maintaining that “suspension of disbelief”?

Tomb Raider is one of the best games I’ve played. The verb is important, as much for what it means for a game as what it means in the context of “acting”, of “role playing”. I implicitly entered into a contract with the game, if it would provide me a consistent structure by which to contextualise my actions I would play within that structure. My behaviour when I was in control of Lara, and her behaviour outside of my control reinforced each other, strengthening both aspects. It required no more effort that playing “cops and robber”, I had a role and I played to that role, the result was an alignment of player and character frames unlike any I’ve experienced.

4 replies on “The role of her life.”

Thanks for a great post. Tomb Raider is certainly all about LCs journey. The story is there to be the fuel that lights her fire.

Excellent post. Thanks for drawing attention to the work of Worch and Fine. It applies to my recent experience playing JRPG’s… often, in the character frame, I’m supposed to be pursuing some urgent plot development — rescuing someone whose plight is alarming and time-sensitive — but in the player frame, I know I have to grind for two hours (or two days in-game time) to be ready for the boss fight that will inevitably ensue. It’s interesting to see how some different games (The Last Story, Skyrim, Xenoblade Chronicles) have wrestled with this problem, with varying degrees of success.

Thought provoking and an interesting perspective, but I can’t say I can agree that Tomb Raider succeeds – ‘is one of the best games I’ve played’ – because of this. Rather, it seems like you’re one of the best players of Tomb Raider if that makes sense?

Personally, I have a very mixed opinion of the game for reasons we’ve briefly discussed on Twitter. There are some great parts of the game and I appreciate that it is at least partly a tale of growth and survival, as you say – but it’s not consistent. The first part of the game is about growth, then it just becomes a shooter with some occasional comments. I don’t agree with everything he says, but Errant Signal’s video review goes into this in some more detail.

Tomb Raider always interspaces its combat sections with exploration and environmental traversal; combat never becomes the sole focus. Even late in the game the sections of exploration and traversal remain prominent, frequently lasting longer than the combat encounters they bridge. This is highlighted by the finale which is distinctly split between environmental traversal and combat.

That said, Tomb Raider could have ended after the Solarii Fortress and might have been a better game for it. What comes after that is a switch in Lara’s character from survivor to saviour that doesn’t directly get dealt with for several hours. It’s only during the conclusion (really from the Beach onward) that Lara becomes directly proactive, signifying the marked change in her personality from the opening.