In order to consider and analyse the explorative form of games it is necessary to present the game mechanics, the logical game space, in some visual manner. The interconnected nature of objects and actions, nouns and verbs, within a game can make any attempt at a complete representation of the entire possibility space prohibitively complex; therefore some degree of simplification is required at least in order to establish a conceptual framework on which to build.

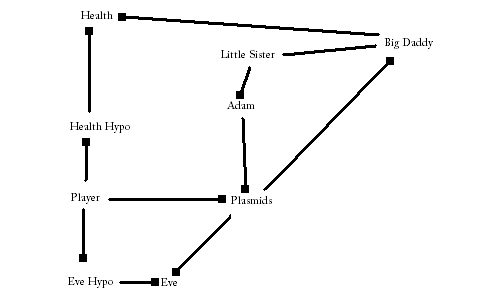

As a first step towards such a visualisation I have started with the previously discussed example of BioShock. Restricting interactions to only those specifically related to the relationship between the player and the Big Daddy leads to a version of the graph depicted below (Click through for a slightly larger version).

This should be understandable to anybody familiar with BioShock. I have intentionally left out a number of mechanics and relationships in order to focus on one specific aspect of the game and see if examining this in isolation can help to gain an understanding of the way in which the game communicates meaning. I have chosen to focus on this aspect in particular, as it directly involves the Little Sisters and Big Daddies who could be considered the emotional, conceptual core of the game.

With a little thought this graph could be expanded to include all the major interactions available to a player in BioShock. Weapons function in a similar fashion to Plasmids, except with Ammunition available either from the environment itself or through the expenditure of Money found in the environment; both such items can also be found on defeated Enemies. Using the existing graph as a starting point it should be fairly straightforward to create a similar graph for the relationship between the Player, their Weapons and their Enemies.

What purpose is served by representing the gameplay of BioShock in this fashion? Before I answer that I would like to compare this graph with a similar one created for Beyond Good & Evil.

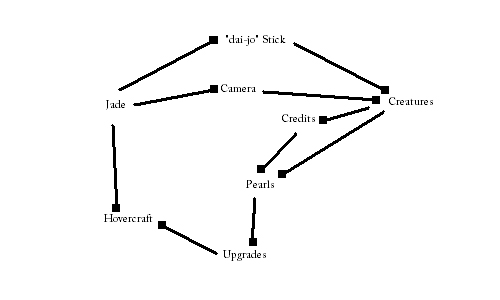

The range of objects and interactions in Beyond Good & Evil is such that, although still simplified this second graph is very nearly complete. The main missing elements are the ability to interact with characters within the world, the special-case mini-games and the ability to use Credits to upgrade your “dai-jo” Staff and purchase tools to improve your ability to locate Creatures and Pearls. A basic understanding of the game should be enough to understand how such elements would modify the existing graph.

Even in this simplified form, it’s possible to see some similarities in these two superficially dissimilar games. As a core part of their mechanics both involve the collection and expenditure of resources: Adam and Eve in the case of BioShock; Credits and Pearls for Beyond Good & Evil.

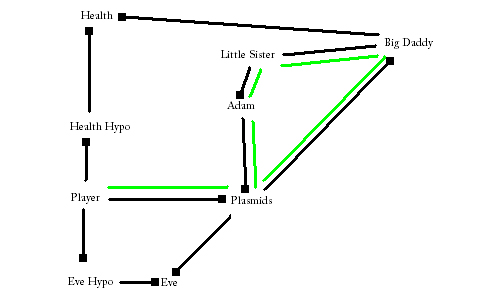

If we consider the way in which the player interacts with these resources and how they flow through the game space we can generate a graph something like the following for BioShock.

Excluding Weapons for a moment the core resource in BioShock is that of Adam. It is used to purchase or upgrade Plasmids which are then used in combat to defeat Big Daddies and thereby gain access to Little Sisters who provide a degree of Adam which starts the cycle afresh. There are other interactions available and other uses for Adam, each of those introduces a modification to the core resource cycle either by increasing the Player’s direct abilities in combat or allowing them to gain access to more resources which in turn are used to increase their combat effectiveness.

The core resource cycle, the core play, of BioShock revolves around engaging in combat for the singular purpose of becoming better at engaging in combat in the future. There is no other use for the resources available other than either directly or indirectly influencing your combat effectiveness. It is effectively a closed cycle, a treadmill.

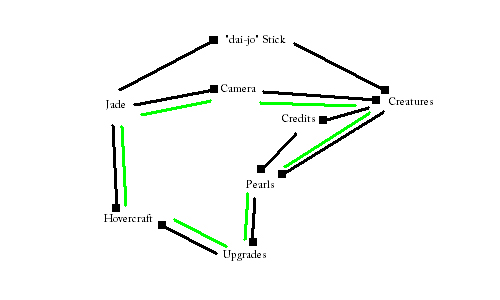

Compare this to the core resource cycle for Beyond Good & Evil.

The main methods for acquiring Credits and Pearls in Beyond Good & Evil are combat or using your Camera to take picture of Creatures in the world. The former provides a relatively low number of credits, the latter a variable number of Credits (approximately 200 – 2000, though always significantly more that could be gained through combat) for each unique Creature. In addition after every ten photos taken you will earn a new Pearl. Additionally some Creatures, specifically Boss or Mini-Boss characters, will drop a Pearl, finally Credits themselves can also be used to purchase Pearls.

In the world of Beyond Good & Evil Pearls are contextualised as a black market currency – despite apparently being almost everywhere – and only one location will allow you to purchase anything with them: Mammago Garage. Here you can use Pearls to upgrade your Hovercraft which allows you to unlock new areas of the environment in which to explore, find new styles of play, and expand the narrative.

Everything in Beyond Good & Evil revolves around locating Pearls, which themselves only have one use, that of increasing your ability to explore both its world and its narrative. Though the Hovercraft can be used to defeat some Bosses and acquire Pearls that is not its primary function. The resources in Beyond Good & Evil are used for something other than directly gaining more resources, the core resource cycle could be considered an open cycle.

Because acquisition of resource is at the core of both games it seems valid to use the resource cycle of each game to analyse what they appears to be saying, their meaning.

In terms of the game mechanics it could be said that:

-

BioShock‘s meaning is that acquisition of wealth or power is only important in so far as it can allow for the continued acquisition of wealth and power.

-

Beyond Good & Evil‘s meaning is that the acquisition of wealth is only important in terms of the freedom it provides.

Though based on a simplified representation of the game space it is still an interesting first step in an analysis of the inherent meaning of particular game mechanics and game systems.

5 replies on “Exploring Meaning.”

Very interesting idea, but the Bioshock examples seems to be leaving something out. While it’s not strictly necessary to collect Adam in Bioshock, it certainly makes progression through the game (and being able to further explore its story and locations) much easier.

The barriers in BG&E have a binary relationship with the resources (they exist before you collect X, the don’t after). Bioshock’s start at being somewhat impeding and decrease gradually as you become more powerful.

I’m not sure if this changes the conclusions you’ve drawn, but it seems worth of consideration (and maybe you already did and just didn’t feel it bore inclusion).

I liked that. I was expecting something abstract and wordy instead.

[Caveat: haven’t played Bioshock]

So what you’ve suggested is that games can be shown to have “interaction loops” which can be explored. Re. this:

– You’ve got the graphs as actual loops, but it make sense to have some terminating lines, e.g. leading to “Death” or “Victory” both of which are explored by the player in many games.

– Also, you could build on that idea for including narrative. Something like:

Narrative is “that which describes the (1) values of events and (2) motivation of actions of an interaction loop”.

For example in terms of pure interaction, a Player gets pearls to permit exploration of the possibility of upgrades.

Adding narrative to the mix might be something like

(1) taking into account that the upgrade solves a problem [i.e. its value = that which “needs” to be done], and

(2) You empathize with Jade’s need to overcome problems

You can imagine that on top of loops like you’ve drawn above are a series of annotations on value and motivation.

@Nels: Yes, I did gloss over some elements of both games which I was planning to bring up in a subsequent post but I feel here is as good a place as any.

I found BioShock an interesting example as I believe it is entirely possible to not use any Adam after you rescue\harvest the first Little Sister. All the Plasmids that you need to progress or explore are provided to you (ElectroBolt, Incinerate, Telekenisis), so the only use for Adam is to make yourself better in combat. It will be progressively more challenging if you don’t use Adam but I can remember no situation where it would be a requirement.

Because of that the acquisition of wealth (In terms of Adam) in BioShock is only of benefit to you because it can serve to make you more effective in combat. Wealth is not a requirement but it’s use is limited. You can have freedom without wealth, but it will be difficult.

Beyond Good & Evil on the other hand explicitly gates progression and exploration based on your current wealth. Wealth is a requirement and its use is just as limited. You cannot have real freedom without wealth.

Considering the contextualising narrative of each game those are some interesting and potentially mixed messages they appear to be presenting.

Nice work. I don’t consider leaving stuff out to be a problem … quite the opposite, in fact.

However, I don’t see the nodes and arrows being consistently defined. Perhaps you could enlighten me? In the BG&E diagram, for instance, a great deal of the diagram seems like it models stocks and flows. But parts of the diagram don’t fit, like the Upgrades > Hovercraft > Jade flow, and the Jade > Camera flow.

I think treating each node as a game object is a fundamental unit of gameplay is wrong: rather, there is often a 1:1 correspondance between the game objects and the game’s stocks, flows, and/or other dynamics. But equally often, there is not. The camera, for instance, is really just representation of Jade’s ability to take photos … it is not really a game object in the same sense that Jade’s supply of Pearls is a game object.

If you wanted to make the entire loop like a stock and flow diagram, it would probably look more like: Unexplored area > Creature photos > Pearl > Hovercraft upgrades > Unexplored areas … Jade is absent from the diagram, because she is embodied in the act of traversing the loop.

I just wanted to say that this remains one of my favorite articles I’ve ever encountered on the web. It got me thinking about design in a more organic way: why some game systems feel natural, and some feel awkward.

Take Hinterland as a contrary example: The premise of the game is that the King has appointed you the task of taming a wilderness in his kingdom by building a new settlement there. You kill monsters and construct your city, with kills providing loot/gold and fame, both requirements for expanding your town. Expansion of your town provides you with a greater array of party members with whom you may sally forth and reclaim more hinterland from the vile monsters.

So, great, on the surface it appears the resource cycle is valid as it relates to the themes of the game.

But as it turns out, the only requirement for winning the game is that you kill a certain (artificial) number of monsters. You don’t have to build a single building. Our resource cycle makes the game easier, but it’s not necessary to the core goal of the game. Taken by itself, this would be fine, but in the context of the game world, this perfectly contraindicates the theme. It leaves you feeling like you’re playing a game other than the one advertised, and the theme and setting of the game are diminished rather than enhanced by its mechanics.

See what you’ve done to me? Now I see resource cycles everywhere. Don’t even get me started about Farcry 2…